Colleges and universities must take steps to ensure student safety in the event of an opioid overdose.

by: Wendy Glauser from the RNJ 2019-11-05

The opioid crisis continues in full force, with recent data showing young people to be most at risk of opioid deaths. But places where youth live, study and party – college and university campuses – have been slow to respond, due to stigma

and liability concerns. Now, nurses and other harm reduction advocates across Ontario are calling on all post-secondary institutions to treat naloxone the same way they would epinephrine auto-injectors and automated external defibrillators

(AEDs): as a lifesaving tool that requires widespread availability and training.

From 2013 to 2017, opioid-related hospitalizations across the country increased by 53 per cent among young adults aged 15 to 24, according to data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information. A study published last year in the

Journal of Addiction Medicine found that, in 2015, more than one in nine deaths among 15- to 24-year-olds were opioidrelated – up from one in 15 deaths five years earlier.

Nationally, hospitalizations due to opioid poisoning increased by 53 per cent among teens and young adults aged 15 to 24 (2013 to 2017).

Source: Canadian Institute for Health Information

This reality has prompted the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) to launch its Carry It campaign. A national initiative to promote naloxone on campuses, the campaign comes with a toolkit that anyone connected to a campus can use to advocate for and develop an opioid overdose protocol. It also includes talking points on how to counter fears from Registered Nurse Journal decision-makers, information on how to acquire naloxone, who to train, and more.

“Student body organizations across the board have told us there’s a real need here,” says Fardous Hosseiny, CMHA Interim National CEO. “Most of them have heard anecdotally about people using in the dorms or washrooms.”

“In the library, you might find students sleeping in corners or on the chairs, because it’s a quiet space. After someone has been there for six or seven hours, you start to question, are they sleeping or are they unconscious?”

According to surveys in Canada and the U.S., five to seven per cent of post-secondary students surveyed reported using prescription pain relievers that were not prescribed to them within the past 12 months.

Source: Canadian Mental Health Association

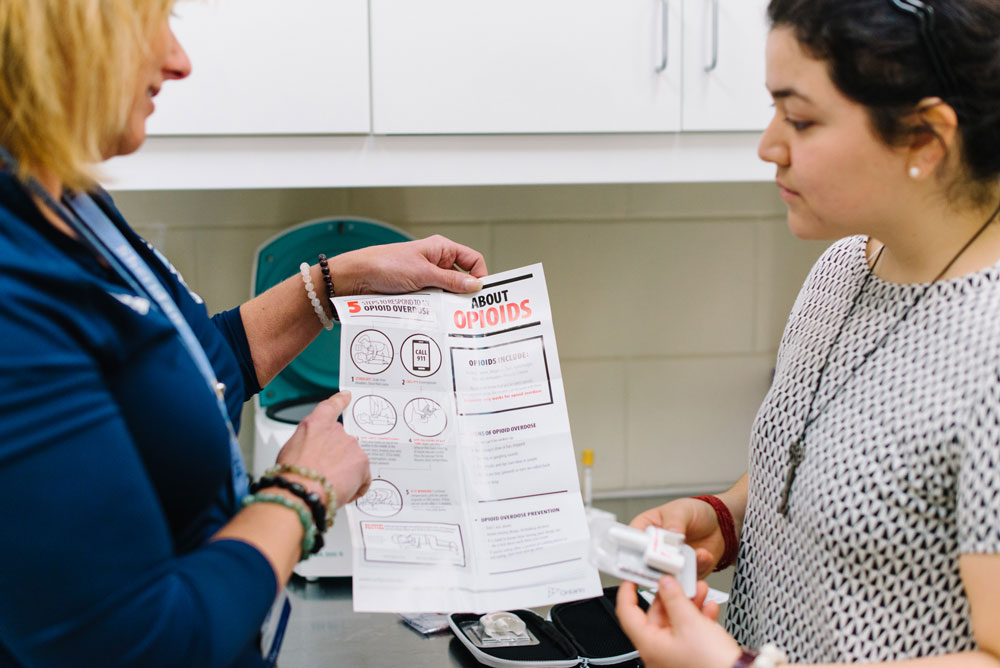

Tammy Datars, campus RN and president of RNAO’s Ontario Campus Health Nursing Association (OCHNA), offers naloxone training to staff and students on Sheridan College’s three campuses.

RN and harm reduction advocate Hannah Stahl, who graduated from Toronto’s Ryerson University this year, says students are not the only ones who can struggle with opioid addiction on campus. Educators or staff may also fall victim. “Opioid use is so widespread and includes people who don’t fit the archetype of what you think a drug user looks like,” she says. Despite the crisis, post-secondary institutions have only just begun to roll out naloxone programs. Many campuses still don’t have naloxone available, or only have a limited supply. “When we did our environmental scan in 2018, we heard that some (post-secondary institutions) had made it a priority, but the majority did not,” says Hosseiny.

Tammy Datars is a campus nurse at Oakville’s Sheridan College and the president of the Ontario Campus Health Nursing Association (OCHNA), an RNAO interest group that formed in 2015 to represent the voices of these specialized RNs. She explains nurses who want to implement harm reduction services face stigma that their efforts could somehow tarnish a school’s reputation. Liability is also an issue. When CMHA researchers spoke with administrators as part of the environmental scan to inform the Carry It campaign, “their biggest concern was around liability,” Hosseiny corroborates. “And we responded by saying the most dangerous thing you can do during an overdose is nothing.”

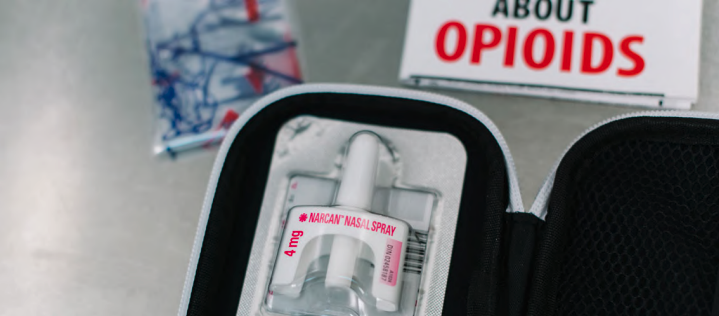

At Sheridan, Datars and other advocates made the case that not having naloxone available creates more liability than having it. “Our legal team agreed and our insurance providers are covering all staff and students in the event they ever have to administer Narcan [naloxone],” she says. Thanks to Datars’ advocacy, naloxone is available all over Sheridan’s three campuses, including in residences, athletic facilities and libraries. “In the library, you might find students sleeping in corners or on the chairs, because it’s a quiet

space. After someone has been there for six or seven hours, you start to question, are they sleeping or are they unconscious?” she says. Datars has provided training to resident assistants, security personnel, librarians, social work students, and others about how to recognize someone who could be unconscious from an overdose, and how to administer naloxone, via the nasal spray. “It’s daunting for people to give someone a needle if they haven’t done that before,” she says of the decision to use the spray.

In 2018, Ontario saw 1,473 deaths from opioid overdose, which is an average of four people each day.

Source: Public Health Ontario

Leigh Chapman, an RN, harm reduction advocate, and recent PhD graduate from the University of Toronto’s Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing, says naloxone should be available on “every corner of a campus” because “irreversible brain death can occur within minutes” in an opioid overdose.

She’s concerned that the opioid overdose protocols on campuses are haphazard across the country. “It’s shocking to me that there’s no standardization in the midst of the worst public health crisis of our generation,” she says. “If I were a parent with children going to university, I would be appalled.”

At Ryerson, it was the student community, especially nursing students, who led the charge. Stahl was part of a campus group of harm reduction advocates who organized a training session for nursing students on how to administer naloxone (nurses were given naloxone to carry with them at the training). But Stahl points out that she’d prefer if it were the university that was leading naloxone training initiatives. Stahl’s group also advocated for Ryerson to include a ‘Good Samaritan’ policy in its code of conduct, to make it clear that someone who overdoses, and those on the scene, won’t be expelled or suspended if they are in possession of drugs. The policy ensures that fear of consequences isn’t a barrier to getting help. The CMHA Carry It campaign toolkit recommends all universities introduce this policy.

In addition to advocating for more standardization in harm reduction policies via its online toolkit, the CMHA campaign will be more noticeable on the ground in the coming months, says Hoisseny. One idea is to create “pop up” booths or tents for distributing naloxone kits and training students and staff in their use, he says. CMHA is also in discussions with Narcan, the maker of the nasal form of naloxone, about getting bulk supplies. Hoisseny says he would love for campus nurses to be more involved in the campaign. “Nurses play a big role on these campuses. We’d love to work with them to get this information out there.”

Bradley Manuel, president of RNAO’s Nursing Students of Ontario (NSO) interest group, and the student representative on the association’s board of directors, says he carries injectable naloxone and plans to look into policies for naloxone on campus with NSO. He appreciates the Carry It campaign is distributing the nasal version because, in his experience, it isn’t easy for students to access. “The only one they had at the pharmacy was the injection one,” he says. Not only are many non-nursing students uncomfortable administering a needle, it could be difficult for anyone to use when intoxicated at a

party, he points out.

New Brunswick NP Kelly Dunfield launched Be Ready to make communities safer for those who suffer from anaphylaxis and opioid overdoses.

While the national campaign aims to put naloxone into hands, Kelly Dunfield, a nurse practitioner in New Brunswick, wants to make sure naloxone is up on walls. Four years ago, she launched her company, Be Ready, to provide epinephrine auto-injectors in clearly-labeled cabinets that can be mounted on the wall. The cabinets sound an alarm when they are opened.

The highest number of alarmed naloxone kits purchased by a single post-secondary institution in Canada: 17

Source: Be Ready Health Care

Dunfield, a former emergency department nurse manager and current head of an NP-led clinic, started the company after hearing about a child who died when an epi-pen wasn’t available. After hearing about Be Ready’s epinephrine cabinets, Corrections New Brunswick reached out to Dunfield to request alarmed naloxone cabinets, which cost $240 each, but don’t include the naloxone, which is available free at most pharmacies.

Dunfield says it’s important for stationary naloxone to be available on campus because it can take too long to dispatch a security guard or other staff member or student who is carrying naloxone. “If you have it centrally located, visible and accessible, then people learn over time where it is.” In addition to the kits, Be Ready also sells ‘Naloxone’ signs that can be placed above the cabinet, visible from three directions.

18 months: The amount of time before naloxone expires and must be replaced.

Source: Canadian Mental Health Association

“It should be part of your regular checks as if you would be checking the AED pads or AED alarms,” she says. Datars hopes that in the next few years, naloxone is “everywhere it could be needed” on campuses. “There’s no reason for any post-secondary institutions to not have it. Ideally, it sits there and collects dust. But it should be there if we need it.”